Organisational Change Management in the Context of DevSecOps

Introduction

In this post I will give an overview of what Change Management is and two frameworks I have used in the past to help me make an impact with DevSecOps. The first is the Three Level Culture Model by Edgar Shein which can enable simple assessments of culture and helps you understand your playing field. The second is Kotter’s 8 Steps for Change by John Kotter, this one I have included in my conference talks, it is a great simple model to understand the extra activities and ordering of a change programme. Understanding and learning about Change is vital to any transformation project and I hope you find this of value (or at least interesting).

What is Change Management?

When discussing Change Management with the current generations of technology professional, many are likely to assume that we are discussing concepts like ITIL and how to manage technology change to production systems. Technology is sneaky like that, stealing words and changing what they mean (I’m looking at you “crypto” :eyes:). But before ITIL, Change Management had a different meaning, it was the study of organisational change, how do you change cultures and people.

Change Management is a series of practices to help deliver transformational changes to an organisation. Change is a fundamental response by an organisation reacting to environmental stimuli, such as technology innovation, new competitors, or war - but…the thing is… we are not particularly good at it. Studies from McKinsey in 2015 show that 70% of companies fail in their change initiatives (McKinsey 2015). Change can be complex, multi-faceted and time consuming (Kotter 1999), coupled with a high rate of failure, these ventures are considerable risk, thus Change Management skills are used to increase the chance of success.

And yet in a field such as technology, where we are implementing change continuously, you have probably never been introduced to the practice!

Assessing Culture

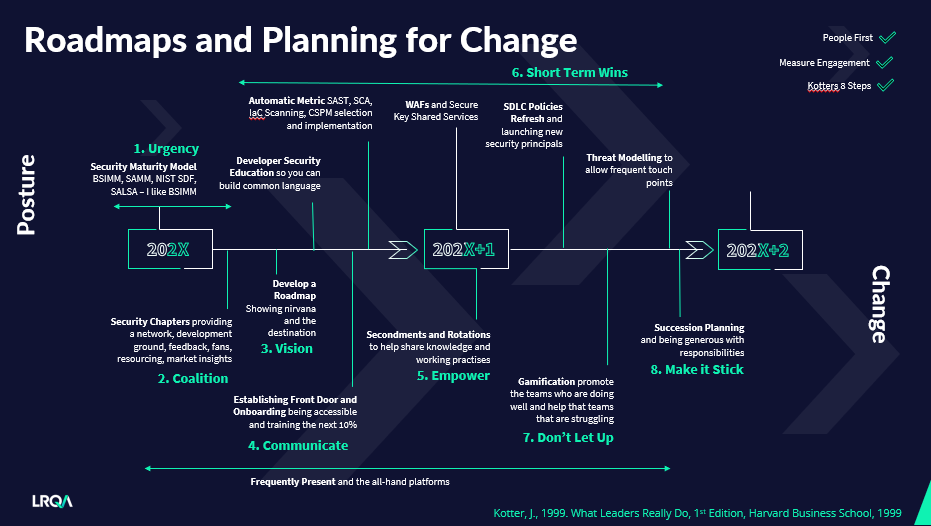

Before we talk about change models, it is important to be able to assess a culture - you need to be able to describe that for which you are aiming. This is made slightly tricky as “Organisational Culture” does not have a concrete definition, but Edgar Schein makes an attempt at this with the words “the underlying beliefs, assumptions, values and ways of interacting that contribute to the unique social and psychological environment of an organisation.” (Schein, 1985). Continuing with Schein, he also proposed the Three Level Culture Model as a way of describing a culture as shown in the diagram below.

Artifacts being the tip of the iceberg - visible out of the water - the tangible and easily observed evidence of culture. This is the brand, the uniform, the benefits, offices (or not), slogans and PR. The external signals that an organisation emits.

This is followed by Espoused Values of the organisation such as strategy, values, principals, and the various other evidence factors that can be gathered in a company’s annual report.

Finally, we have the murky underworld of Basic Underlying Assumptions which is the status quo of the organisation, only visible to those who have been attached to the social fabric of the organisation. This layer is the undocumented and deep rooted “that’s how things are done here”, the prejudice and bias. The hardest layer to articulate and to change.

In the Context of DevSecOps?

The Three Level Culture Model can be used against any magnitude of social structure, such as a development team. The reason you want to do this is to enable insights into how you might influence and nudge the team as part of your DevSecOps transformation. All teams have subcultures, and a big mistake would be to have a one size fits all approach to change. For example!

Engineering Team - Alpha

Artifacts could be the team logo, such as a tiger, the vocal and opinionated presence in teams’ calls, the general sense of grandiosity and looking down on other teams. These are artifacts because the evidence is visible to those who are not part of this social fabric and are projected by the team, you can receive these signals easily.

Espoused Values could be the teams drive to be at the bleeding edge, introducing innovative technology to the organisation and be seen as the “best” team. These are likely values shared within the team and cultivated, one either needs to be close to the team or observe them over a period to pick up these signals.

Basic Underlying Assumptions could be a sense that the rules do not apply to them, security is getting in the way all the time, that the team are technology heroes. These signals are “leaked” through continuous interactions with the team and through conflict.

I will stress, the point of this exercise is not to apply a judgement to a team’s culture, it is merely to articulate, describe, gather insights into it and plan to respond. In this case

- The team is very conscious of its status amongst its peers, they need to be seen as the best, so efforts in gamification are likely to work well.

- The team are seen as early adopters of innovative technology, so they may be responsive and especially useful if included in trials for products or anything that can be made to feel “exclusive”.

- There is a deep-rooted assumption on the attitude towards Information Security that will need managed. Plan for it, prepare for it and don’t take it personally.

Frameworks do not provide answers, they just structure your thinking to uncover insights which can be used to inform an approach to dealing with the team’s culture. Can you see how some of these insights might change how I roll out a security tool to this team?

Engineering Team - Team Beta

Artifacts In this case the team have an extremely limited presence, little to no intentional signals, but there are other clues we can look to. They do not participate in group calls, they never speak up, cameras are always off for this team. The team are frequently placed last in statistics - either on number of incidents, security issues, technical debt etc. Getting a response from team members can take days.

Espoused Values are tricky in this case, though we can propose there is a value here of team isolation, an “us against them” mentality. There may also be values of survival and short-term thinking if the team are struggling with incidents and technical debt.

Basic Underlying Assumptions again, difficult as we are unable to find opportunities for “leakage”, but we can make assumptions such as fear and distrust against other teams. Fear of further status loss, fear of additional work etc.

And why is that important? It changes how we lead and nudge the team.

- Gamification is unlikely to work here as the team already have a distrust of comparisons against other teams, they may believe the games are not “fair” so why should they play?

- The team are also likely unresponsive to function wide communications, any reporting, or communications from me they won’t not read - those communications are “for them, not us”.

- In the presence of outsiders (me) the team is only going to open (feel safe) if the team outnumber me on a call.

And this is the game - and this is where technology change struggles - there is no one size fits all to change. If you want to make an impact you need to adapt your strategy to each subculture you are dealing with, and models such as the Three Level Model can help describe your playing field.

Culture comes from social structures; it will happen whether we like it or not. You cannot fight it, but you can assess and respond to it.

Kotter’s 8 Steps for Change

One of the popular models that supports Change Management is Kotter’s 8 Step Change Model (Kotter 1999). John Kotter is a Harvard professor and thought leader in organisational change and leadership. Discussed in detail in his book “What Leaders Really Do” Kotter’s 8 Step Model is a series of outcomes that must be met in sequential order in order to achieve a successful organisational change.

I am just going to repeat that - this is not an ala carte menu - you need to hit all the points in the right order, not just the ones you like, and this can take two years. This was the other challenge adapting my approach to DevSecOps, changing hearts requires quite a long planning horizon!

Step 1 - Urgency

Changing hearts requires a story, a narrative, as to why your change matters, why it is important and why it needs to happen now. Before starting a transformation, you need to understand what story is going to carry your work and explain the “why”. You may be gifted with a reason, all too often that could be a breach, but it could also be customer and market demands. Stories that involve business growth, supporting the business strategy, involving virtue, make for good stories. Stories that are driven by compliance, certification (such as ISO27001), or because the “CISO says So” are much harder to craft a story around. Your story is more important than your budget, your team and plan, without one you will face repeated resistance.

Step 2 - Guiding Coalition

There will be those amongst your organisation who will heed your call, these are the DevSecOps advocates, the fans, those who have been championing for this sort of change before you arrived. How do you bring people together under a common cause? it starts with forming a club. This is what security chapters and champions are all about, uniting and forming a coalition, those who will support your cause when you are not in the room and identify with it. Doing security chapters right can take effort and I will include a further post on this topic in future.

Step 3 - Vision

You have your story and have your advocates, now they need to a direction to march. You need to create a roadmap which describes what nirvana looks like and what needs to be achieved to get there, what will be delivered and what measures are going to show the world is moving the right way. A roadmap is like an anchor in the storm that is information security, where security incidents and changing business priorities can derail your teams.

Have a roadmap first, or you will have a roadmap inflicted upon you.

Step 4 - Communicate

This is where I see technology change programmes fail, communication is not seen as the critical component to enabling effective change. All too often it is done a handful of times at the start of a programme, over a single channel, and then ceases. To communicate a change, it must be done repeatedly, your narrative and progress but be done on a frequent cadence by you, there is no such thing as over communication, especially in a remote environment. It also must be done over multiple channels. Your audience will use a variety - some will use emails, some will use Teams, Slack, Yammer, some receive information best at “all hands”. You do not get to pick; the winning strategy is to use them all. A message received over multiple channels increases its credibility.

You must continue to show presence and remind everyone this is still important, it is still urgent, we still need to do this now.

You are leading this charge; you cannot delegate this to a project manager. You also have license to make this fun, stand out and do something differently - if your communications were boring to put together, they were boring to read.

Step 5 - Enablement

Humans crave autonomy. We want to be given outcomes to achieve, and autonomy to get there. It helps us feel in control of how we operate and is linked to job satisfaction (Pink 2018). With DevSecOps we are asking developers and development teams to change, and we need to help them in taking a leading role in this. We can make security tools, education, consultancy and support available but we need to enable teams to run their own tools and process. They will make the tools works for them. There is no better person to secure a system then the ones designing and building it. I am not saying throw tools at teams, I am saying that teams need to be part of the procurement process, the roll out of tools needs to be done in partnership. The team will need your help in understanding what the tool are saying and what needs to be fixed (if something needs fixed at all). Secondments can also work well here, giving a chance for engineers to be part of the security team, understand the threats we face and to building relationships.

Step 6 - Quick Wins

It is not until Step 6 where we start to talk about security tooling! We need to be able to start getting a pulse on the security health of our estate and measures we can use to show return on investment (ROI) and show the world is getting better. I believe this needs to start with developer education.

If you are given a tool and you do not understand what it is telling you, you will dismiss it as noise. You must start with education.

OWASP Top 10 and understanding the basic of common web vulnerabilities. Learn the acronyms and the impact of the vulnerabilities, learn why they are bad and what the bad guys can do. It is also an easy metric to push the right way, it’s a quick win. Once you have that in place you can then move in with a mature security tool. I will write a future post on tooling and what makes a useful tool, but for now I would recommend picking one breed of tool and doing it well. You can go for tools that are closer to developers such as SAST + SCA tooling (Snyk, Veracode, Coverity & BlackDuck etc). These vendors are mature, they support many languages and have integrations to help reduce friction in the SDLC.

Its less about best of breed security tools, and more about adoption. That means onboarding, integrations, speed, and developer experience are more important than how “good” the tool is or the reporting features.

You can also pick tools that are closer to operations, CNAPPs for example, such as MS Defender for Cloud, Wiz, Rapid7 etc. There are pros and cons to both, but I would not recommend doing both. Do one breed of tool now and do it well, future tools can be integrated as your developers mature.

The goal of these tools is not to get to zero, it is about being able to take an easy pulse of your estate and to show the world is going the right way, to demonstrate ROI and to promote your quick wins. I will explore reporting further in a future post.

Step 7 - Don’t Let Up

You need to plan for people disengaging with your change overtime. You will be competing for change with other initiatives that will have the benefit of being novel. You need to plan for this and find ways to keep people interested. Gamification is a useful technique to bring into your programme once the tools are in place. Status plays a big part in an engineering organisation and being able to provide a relative view of teams and how the compare, can spur competition. Even the teams that do not want to play, certainly do not want to lose. It does need to be done with care and respect, some teams will inherit a legacy part of the estate that is difficult to work with and a hotbed of risk. By gamifying the delta, the improvement each month, and rewarding the teams that improve their estate the most, we can keep the game fair, and everyone can stay in the game.

Step 8 - Making it Stick

The final part of the steps for change is being able to make the system continue without your involvement. For me, this is about developing the next leaders who can take the flag from you and continue to promote secure practices. This takes coaching, mentoring, and developing a talented team, but that is also a post for another day.

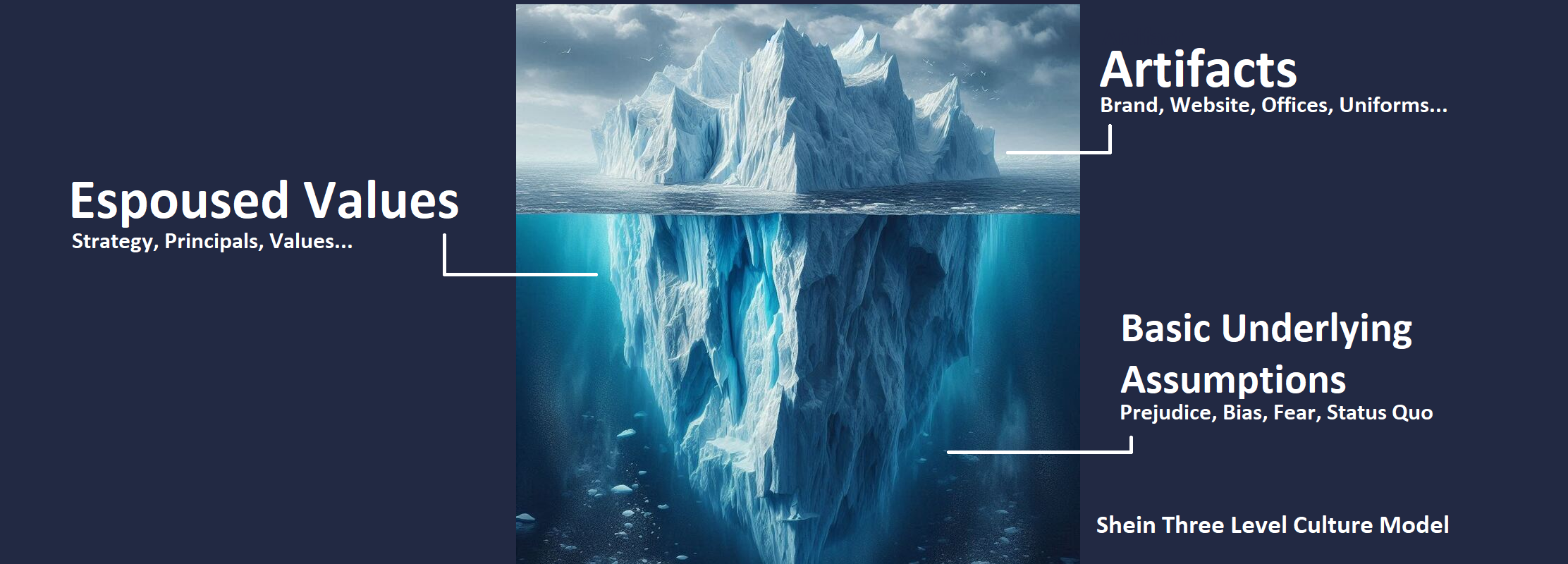

Bringing it all together looks a little bit like this!

I have a video talking through this from BSides Bristol (2023), you can find a link to in on YouTube from my speaking page.

Summary

In the post we touched in how we could use Shein’s Three Level Culture Model to help assess the culture of a team, function, or organisation. The model does not provide any answers but can help us gain insights into how we might try and nudge a team on the path to secure development. We also looked at Kotter’s 8 Steps for change and how they can be applied to a DevSecOps transformation. My hope was to give you an overview and with time we can explore each step-in detail with future posts. I hope that was useful and interesting, thanks for reading! Seb

References

- Kotter, J., 1999. What Leaders Really Do, 1st Edition, Harvard Business School, 1999

- McKinsey, 2015. Changing change management. Available from: https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/leadership/changing-change-management [Accessed 08/05/2024]. [Online].

- Pink, D., 2018. Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us, Canongate Books.

- Schein, E.H. (1985) Organizational culture and leadership, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.